PART FIVE: METAL CONCERTS FOR MIGRAINES

This is the fifth of an eight-part patient advocacy manifesto, I Dissent.

This is the fifth of an eight-part patient advocacy manifesto, I Dissent.

“We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people.” ~ JFK

FOR THE SAKE OF PRINCIPLE OR VIRTUE

I recently participated in a conference for patient advocates to discuss the obstacles facing patients. One of the panels of the conference was focused on patient advocates discussing healthcare disparities – which, undoubtedly, exist in the modern healthcare paradigm, a time when health insurance costs are at a premium, access to therapies is dependent on coverage, and the therapies that exist are, at best, suboptimal. And those three factors are just scratching the surface.

In the beginning, the host came on to introduce the panelists: introduce yourself, announce your pronouns, and share your land acknowledgments.

This was new to me: land acknowledgments? I listened on.

"Hi, my name is (insert name here), my pronouns are (insert here), and I reside on occupied Lenape (or other tribal nations) land."

Hmmm. I thought. That's new. I wonder if they are going to talk about the healthcare disparities that indigenous people face, and the desperate need for better therapies to treat diseases that indigenous people die of at higher rates?

After all, Native American people have higher rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and sepsis than other Americans. Unsurprisingly, due to these disparities, their life expectancy is 5.5 years less than all other races in the US.

If this would be the focus of the panel discussion, it would be quite a great hook to acknowledge the land of indigenous people. We all know the terrible history of colonialism, its impact on native populations and the ripple effect that has had, and continues to have, on generations of indigenous descendants.

That is not where the conversation went. In fact, the healthcare disparities of native people did not come up at all. Instead, the focus was on the obstacles that the individual panelists face because of their intersectionality, as well as how we live in an ableist world, and that we need to unpack our own internalized ableism in order to accept the hand we have been dealt — and that is to own our diagnosis as part of our identity, as much as our fixed traits of race, sex, sexual orientation, and ethnicity.

With this in mind, I wonder: have we lost sight of the original intent of patient foundations?

NO GOOD DEED GOES UNEXPLOITED

On January 12th, 1951, Dr. Sidney Farber spoke at the New York Academy of Medicine to give a talk about how cancer care had entered the era of chemotherapy, which he is considered the father of. Instead of basking in the glory of his contribution to this research, he focused on the mission: how contributions made over the centuries, and from a variety of disciplines, led to the success rates of the time.

“Our discussion tonight is based upon research – most of it no older than 10 years, and as recent as this moment. But it is only the breakthrough which has come in these last few years. What has been accomplished is based clearly upon contributions, made through the centuries and from a variety of disciplines, by individuals and institutions scattered over the world.”

He went on to make a point to note that we have further to go.

“All anti-cancer effects produced by chemical compounds are temporary in man,” he says, “with effects lasting from weeks to months – and only occasionally for periods as long as six years.”

As a physician-scientist, Dr. Farber knew that surgery and radiation were not successful in blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma. At the time, doctors knew that those cancers were caused by immature white blood cells that began in the bone marrow and crowded out healthy white cells – making it impossible for patients to fight disease.

Dr. Farber hypothesized that if folic acid was blocked (which he knew stimulated the bone marrow), that could prevent the blasts of immature white blood cells from invading, and therefore, stop blood cancers from becoming fatal. He went on to conduct a trial of sixteen children using the drug Aminopterin, known for its folic-acid blocking ability.

Ten of the sixteen pediatric patients went into remission.

In that same year, Dr. Farber established the Children’s Cancer Research Institute (now known as the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute). He knew that medical research needed better funding, and to do so required better publicity to highlight the necessity of research.

Enter Einar Gustafson, or ‘Jimmy’ as he became known: a 12-year-old boy with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

At the time, cure rates were between twenty to thirty percent. Now, they stand at ninety percent, thanks to investments in research.

The Variety Club of New England was an early supporter of Dr. Farber’s mission and put together a revolutionary method of raising money for cancer research: they had a well-known radio personality, Ralph Edwards, broadcast directly from Jimmy’s hospital bed to let the nation know of Jimmy’s one request: a TV set to watch the Boston Braves while he was stuck in the hospital.

Ralph Edwards let the nation know: if we raise $20,000 for cancer research, Jimmy gets his TV set to root for the Braves while we all root for Jimmy.

Little did Jimmy know that soon, one by one, the Braves would be piling into the hospital room to surprise their young fan.

The funding poured in, and within a year, what became known as ‘The Jimmy Fund’ raised $231,485.51 for cancer research. To date, The Jimmy Fund has raised 150 million, which has funded significant research in chemotherapy for children and reduced the death rate of some childhood cancers from 90% to 10%.

Thus, the boom of patient foundations in the decades that followed.

Ribbons, walks for the cure, galas: all opportunities to market different diseases to raise funds for research.

But how much of that funding actually goes to new research? And who, exactly, is contributing to the patient foundations?

BY THE GRACE OF THE REBELS AND TROUBLEMAKERS

When Brian Wallach was diagnosed with ALS after the birth of his second daughter in 2018, the former Obama adviser and prosecutor, alongside his wife Sandra, also an Obama aide, realized there was an opportunity here — a message in the misfortune — to use their Washington know-how and expansive network to form a nonprofit that would revolutionize patient advocacy, create a new call to action for investing in translational research, and expand access to novel therapies.

The foundation, I Am ALS, has mobilized ALS patients and caregivers with actionable steps and publicly called on Congress to do the right thing: take action now for patients today, and to create a future where ALS is safely in the trash bin of history. Brian and Sandra have gotten this far by refusing to take “no” for an answer — and while discussing the word ‘incurable’ in its use for ALS, during his congressional testimony, Brian said: that’s only because it hasn’t been cured yet.

Born out of Brian’s grit and his wonderful stubbornness to change the status quo, the efforts of the I Am ALS organization are also necessary. The now lesser-known ALS patient foundation – the ALS Association – was met with fierce backlash from the ‘pALS’ (patients with ALS) and their cALS (caregivers) for what patients and caregivers have perceived as a lack of advocacy on behalf of patients and a failure to properly invest the $115 million it raised from the Ice Bucket Challenge — as eight years later, $90 million remains.

Not to be deterred, the pALS came together over the last two years, organizing virtual events and mobilizing not only their community, but the entire country. They tagged journalists and Congress on Twitter and raised some good old-fashioned trouble.

In her New York Times article, “A New Testament to the Fury and Beauty of Activism During the AIDS Crisis,” Parul Seghal writes of the ACT UP activists:

“All of them became autodidacts in drug research, policy, media relations. It seems to me that some of what converted people to the cause was ACT UP itself — its energy, the way it got things done, the magnetism of the activists, their fury and their beauty.”

Taking a page out of history, ALS patients — many no longer able to speak or move — became autodidacts as well, and in doing so, the pALS and cALS have done what their own patient foundation wouldn’t: wrote legislation to fund ALS research and expand access to clinical trials.

One campaign organized behind the scenes through direct messaging on Twitter included their #NoMoreDead campaign, where the community put red tape over their mouths with the word ‘DEAD’ written across it, calling for Congressional ALS hearings to expand access to current investigational therapies.

Meanwhile, the I Am ALS team organized virtual events such as the one with Congresswoman Rose DeLauro to allow patients and caregivers to share their stories to highlight the necessity of advancing research on ALS and expanding access to trials currently in clinical trials, saying, “If it’s good enough for Phase 3, it’s good enough for me” — not missing a moment to point out the irony of the FDA ensuring the safety of therapy for patients with a disease that is going to kill them, and for which, there is no other therapy.

Father, husband, and ALS patient Corey Polen worked with Brian Wallach, the I Am ALS team, and Senator Braun to write the Promising Pathway Act. The bill would expand access to investigational therapies for patients with serious and life-threatening illnesses by requiring the FDA to provide provisional approvals for therapies that “demonstrate substantial evidence of safety and relevant early evidence of positive therapeutic outcomes.”

Meanwhile, Brian Wallach and the team also worked together to write their key legislation, “Act for ALS,” which was passed with complete bipartisan support and signed into law by President Biden with pALS and cALS Zooming in from all over the country. According to STAT News’ Lev Facher: “The legislation will fund $100 million worth of ALS initiatives each year, including new federal research grants, a public-private partnership between the government and drug companies aimed at developing ALS cures, and money to help patients access experimental treatments even when they’re not eligible for a clinical trial.”

This is the new face of patient advocacy, and it is high time that patients and caregivers from all communities end their call for ‘awareness’ and move toward action.

What’s more, the Autoimmune Association supports an ongoing effort to engage with researchers in academia and industry to provide patients the opportunity to learn about novel therapies and give new startups a voice to speak directly to patients about the future of healthcare.

These are two wonderful examples of how a patient foundation should function.

Sadly, I have found that these are diamonds in the rough and set the bar quite high.

Much like the pharmaceutical industry, there is a business that needs to be maintained for patient foundations who are charged with solving the very problem that would jeopardize their existence. Rather than meaningful action that ensures a future where patients are no longer in need of a patient foundation, instead, there are ‘Walks for the Cure’ for patients with arthritis, which, to me, is the equivalent of holding metal concerts for migraines.

Patient foundations are often run by MBAs, putting the impetus on profit rather than progress. And, as you can imagine, sticking a pink ribbon on everything under the guise of ‘research’ is undoubtedly a profitable shtick to get behind — stick those pink ribbons on everything from jewelry to stationary to make a buck in exchange for reminding those who are suffering, or have suffered, an opportunity to look down at their hand or their pen and remember their greatest medical trauma – as satirically written by Gila Pfeffer in her open letter to Tiffany & Co.

According to Kaiser Health News, drug-makers gave more than $58 million to patient foundation groups in 2015 alone, as reported by financial disclosures in KHN’s ‘Pre$cription for Power’ database. The database’s purpose is to “track the little-publicized ties between patient advocacy groups and drug-makers.” KHN then poses the question: are patient organizations pushed to put the interest of Big Pharma ahead of the patients they represent?

In 2015, the American Diabetes Association received $4,100,456 from pharmaceutical companies, and that year, their overall revenue was $180,803,003.

That year, the ADA gave $36 million in grants – almost all of which ($35.7 million) went to the Diabetes Association Research Foundation, which distributed .83 cents on the dollar ($29.6 million).

The maker of Humalog, Eli Lilly, gave $2.9 million to the ADA that year. In the last twenty years, Eli Lilly has hiked the price of Humalog 30 times, according to IBM Watson Health.

Which leads to the greater question: is investing in research to cure disease still the mission?

It likely boils down to the same problem we now face with the lack of research into newer, more effective antibiotics. The CDC recently reported that every fifteen minutes, one person in the US dies from an infection that antibiotics can no longer treat effectively – which is 35,000 deaths per year. Drug resistance is a global crisis, but unfortunately, not profitable: Kevin Outterson, a Boston University professor specializing in antibiotic resistance recently told Sigal Samuel in his reporting for Vox that: “This is a product where we want to sell as little as possible,” Outterson explained. “The ideal would be an amazing antibiotic that just sits on a shelf for decades, waiting for when we need it. That’s great for public health, but it’s a freaking disaster for a company.”

For “Big Pharma,” cures aren’t profitable, and their grip on patient foundations is strong. Most of the events held by patient foundations are sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. A 2019 ‘Commitment to the Cure’ gala was sponsored heavily by Pfizer, the maker of the “biosimilar” to Remicade, known as infliximab, and newly approved Inflectra, which is used to treat multiple inflammatory diseases at the cost of thousands of dollars per month per patient.

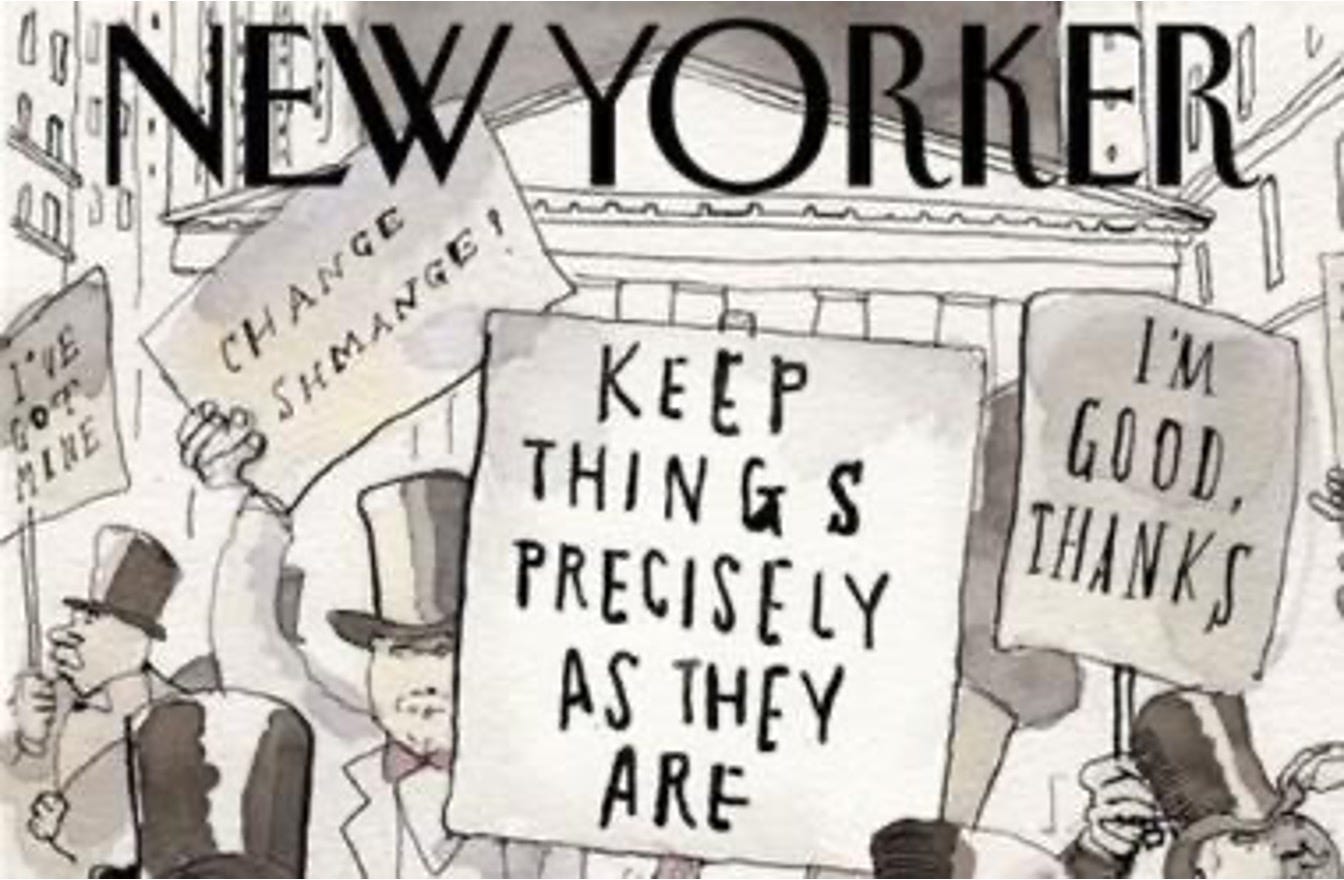

Having pharmaceutical companies sponsor patient foundation events for “the cure” discourages market disruption, and the cure to a disease that rakes billions of dollars in for those same pharmaceutical companies is, indeed, a disruption. The cure should always be disruptive to the status quo, and never contingent on it.

One unintended problem is that patients attach themselves to these organizations, and believe they are somehow going to do more than provide community and education – that they are going to significantly contribute research to new cures.

Patients of the nation need to understand that while those organizations can provide a wonderful platform for community and education, their money and fundraising efforts would be so much better spent by going directly to medical research institutions.

We need to get back to our roots of disease advocacy and look back to The Jimmy Fund as our model for funding research: the lion’s share went into medical research and saved millions of lives in doing so, and massive strides were made in a matter of a decade.

When we look at what the AIDS activists accomplished in the 1980s and how the ALS community rallied together to use this model to mobilize and enact legislation, it is a wonder why these two communities demand the right to their lives — while other patient communities are adopting disease as identity.

It can only be inferred that the ALS and AIDS activists do so because mortality is staring them in the face, like they are looking down the barrel of a gun, not knowing when the day will come that it will fire, extinguishing the light of their existence. For them, time truly is of the essence.

Yet inflammation kills us too. But we die slower.

MISSION: RE-EDUCATE THE ABLEISTS.

What has resulted from the lack of regulation, excessive profit with little oversight, and intermingling of the pharmaceutical industry with both nonprofits and government has led to a narrative of disease as an unalterable, fixed trait, and a marker of identity that needs to be protected from the ableist system that seeks to oppress it.

Meanwhile, nonprofits and pharmaceutical companies provide empty statements of acknowledgment that tell the patients that they are on their side and fighting on their behalf, but without investing in and/or highlighting novel therapies and/or cures that could enable patients to thrive sans dangerous side effects, such as the potential for rare cancers and fatal infections.

Instead, these empty statements of acknowledgment continue, and include hosting galas to raise money for foundations that are titled things like "Commitment to the Cure," — but not to talk about the cure or novel therapies that could improve quality of life.

Much like the land acknowledgments, these foundations aren’t interested in solving the problem – only acknowledging their virtue in recognizing that a problem exists.

Instead, the narrative is focused on talking about ableism, how to be a better patient, and how to make society adjust to our needs as patients. Obviously, none of this is to say that there shouldn’t be patient protections — i.e., the Americans with Disabilities Act, or 504 plans — but shouldn't there also be a goal of aiming for no longer needing those protections because of better therapies that change our lives, and so that those who come after us never need those protections in the first place?

A foundation's sole purpose for its very existence is to cure disease, but in this paradigm, instead, the foundation sells patients a prescribed identity that tells them to “own” their limitations rather than the foundation investing in novel approaches to allow patients to overcome them.

What results from this is a self-fulfilling prophecy that wraps patients up in policy debates, such as Step Therapy Reform, which protects the established, for-profit system that inherently keeps them sick. While Step Therapy should undoubtedly be banned, as insurance companies have no business controlling how physicians treat their patients, there should be a much greater call to do what their existence is charged with accomplishing: finding better treatment options, and eventually, curing disease entirely.

However, today, advocacy isn't meant to cure disease, it's to fight the abled system that having a disease inhibits access to, and therefore argues for lowering the bar rather than demanding a better quality of life raised.

Further, discussing lifestyle is out of the question, as the suggestion that there is a need to examine what we are eating and how much is an effort to ‘shame’ patients. What’s more, imagine the fool’s errand it must be to go up against the food and beverage industry which has successfully lobbied to allow ingredients such as ‘Yellow Number Five’ or potassium bromate, carrageenan, and emulsifiers in our everyday choices at the grocery store. (Regardless of the behemoth of a fool’s errand that is, it is one that should be done.)

Much like the rest of the conversations happening across the ideological and culture wars that plague the day, there is a lack of nuance that permeates the patient and medical communities. Of course, not every ‘fringe’ idea is valid. It is necessary that all potential treatment options are rigorously tested in random clinical trials, and scientists should be able to articulate the mechanism of action that allows their drug or device to provide clinical benefit. Yet even those that do meet those standards are dismissed.

As we know, in the age of COVID-19, those who are immunosuppressed due to biologics often do not mount an effective antibody response to vaccines, leaving them vulnerable to either developing long-haul symptoms if they contract the virus, or worse, dying from cytokine storm. The accusation from patients is that those who want to get on the other side of the pandemic are “ableists/ableds,” instead of utilizing the opportunity as a rallying cry for funding research and accessing therapies that wouldn’t leave patients immunosuppressed.

It appears that much of this is a matter of developing a coping mechanism to deal with the physical and emotional pain that having a disease causes. Putting the impetus on an ableist system, or by owning a disease as a fixed part of one’s identity, is a way to regain control of a currently uncontrollable beast.

It’s perfectly understandable to get sick and tired of being sick and tired – but imagine what would happen if we all put that same energy into demanding that we have better treatment options that give us the opportunity to no longer be sick and tired.

“Part Six: Shirky Down Economics” coming tomorrow.