How Did You Die?

The brain-body connection and its influence on disease, The Spoon Theory and the (unintended?) subsequent narrative of disease as identity, and the great necessity of grit to forge a better existence.

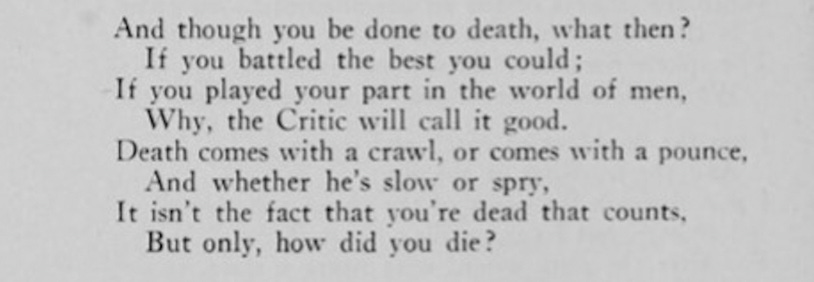

When I was fourteen, my Nan shared with me a poem by Edmund Vance Cooke called How Did You Die?

Diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and crippling inflammatory arthritis at the age of 13, my childhood was turned on its head from one filled with athletics and the outdoors to one where, seemingly overnight, I felt 90, went on heavy duty immunosuppressants, and watched my friend group slip away. To say that I grappled with a new awareness of my own mortality, as well as my sense of identity, is the understatement of the century.

My family had been in the midst of years-long chronic stress that was triggered when my uncle, the patriarch of our family, was diagnosed with brain cancer. Given six months to live, our family’s giant went on to live for five more years. He made the most of what time he had left – a lesson without equal. Even so, as the peacekeeper and mascot of the family, I internalized my own pain and felt all of theirs – so looking back, it was no surprise that the underlying stress manifested itself in a physical form that came down like a sledgehammer and spent the next fifteen years eating away at any semblance of my bodily functions and youth that it could get its grimy little paws on.

The people I descend from form a long line of rebels and hellraisers who went out with their boots on. So, in the early days of my disease, Nan thought this poem would light the fire in my belly I would need to fill the reserves and keep going.

And it most certainly did.

In the years that followed, I went on to make so much out of whatever time I might have, and while doing so, I chased health around the globe until I found it in 2017 in the form of a clinical trial in Amsterdam using vagus nerve stimulation to treat autoimmune disease.

At the age of 28, after 15 years of active disease, 22 failed biologics and immunosuppressants, countless hospital admissions and nights in the emergency room, multiple blood clots, two pyoderma gangrenosums, colitis flares, PICC lines, 20 colonoscopies, arthritis in every large and small joint, and canes, walkers, and wheelchairs, I was finally in remission thanks to a revolutionary new field called bioelectronic medicine.

Bioelectronic medicine represents a convergence of molecular medicine, neuroscience, and bioengineering. Its central idea is that injury and illness can be treated by carefully targeting the nervous system using devices.

Rather than suppressing the patient’s immune system with biologics and immunosuppressants, instead, by modulating the brain’s inflammatory signals traveling through the nervous system to the spleen and other organs, bioelectronic medicine allows the body to achieve homeostasis when inflammation goes into overdrive.

The need for this revolutionary field cannot be overstated. Inflammatory diseases are running rampant. Until the advent of vaccines and antibiotics, the leading cause of mortality was infection. For the last century, however, it has been inflammation. Worldwide, chronic inflammatory diseases kill three out of every five people. Heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and countless other inflammatory conditions have led us to the inflammatory pandemic we find ourselves in today.

When my husband and I returned home from the clinical trial, I reached out to Dr. Kevin Tracey, the founder of this field to thank him for saving my life. Dr. Tracey’s research over the last thirty years has redefined how inflammatory diseases are viewed and treated, first by identifying TNF, a protein generated in the body to prompt inflammation, as the cause and accelerant of disease, then developing monoclonal anti-TNF, which led to two more major discoveries: first, classifying the phenomenon of the body reacting and then overreacting to insult and injury as what is now known as the inflammatory reflex and discovering that the vagus nerve is vital to this mechanism. This major insight was also a boon to the drug industry, which created Remicade, Humira and other powerful (and highly toxic) biologics based on Tracey’s discoveries. Not satisfied with merely creating a new generation of expensive drugs, Dr. Tracey continued his research on the role the vagus nerve plays in inflammation and pioneered new ways to manipulate it and tune inflammation up and down… and without drugs.

As a patient, I knew firsthand the immense for-profit industry that aims to create repeat customers rather than develop effective treatment options that allow patients to thrive. I asked Dr. Tracey what I could do to help expedite Bioelectronic Medicine therapies to more patients and have been working on that ever since.

What I have found over the last five years, though, is nothing short of a behemoth, and a well-oiled machine that not only stagnates progress due to the quid pro quo trifecta between pharmaceutical companies, patient foundations, and government for the sake of profit, but also the trickling down of a narrative from the top that sells patients on the idea of disease as identity and an unalterable fixed trait rather than a faulty operating system needing to be restored.

The consultant/tech guru Clay Shirky says it is the nature of institutions to work to preserve the problem they trying to solve. This certainly seems to be the case in the world of disease treatment.

According to Kaiser Health News, drug-makers gave more than $58 million to patient foundation groups in 2015 alone, as reported by financial disclosures in KHN’s ‘Pre$cription for Power’ database. The database’s purpose is to “track the little-publicized ties between patient advocacy groups and drug-makers.” KHN then poses the question: are patient organizations pushed to put the interest of Big Pharma ahead of the patients they represent?

Meanwhile, in 2020, drug makers spent $314 million lobbying Congress.

Accordingly, by perpetuating the idea of disease as identity, whilst promising to be leading the way toward the solution, those in positions of power delegate their agenda to be carried out by patient influencers to sell a narrative of how glamorous and heroic it is to own the limitations of disease and to fight against the ‘abled’ system that aims to oppress disabled people. As the foundations and pharmaceutical companies share, retweet, and engage with this narrative, it empowers a small group of advocates to carry the torch of having the right point of view.

Much like other political debates that devolve into ad hominem attacks on the other side, i.e., the idea that disagreeing with liberal policies makes a conservative a racist and/or sexist fascist or disagreeing with conservative policies makes a liberal a socialist snowflake or communist, the patient advocacy realm has not been spared the radical response that over-inflates a disagreement into an attack on the patient’s very existence.

Not to overly glorify the nostalgia of yesteryear, but it hasn’t always been this way – somewhere along the way, the traits of grit and resilience has been lost in exchange for not only an acceptance of one’s limitations – but also the need to protect and nurture them. This narrative of disease as identity began accidentally when a talented writer, Christine Miserandino, wrote an essay titled ‘The Spoon Theory.’

As a young woman battling lupus, Miserandino recounts sharing a meal with a friend who asks what it feels like to have a chronic disease. Looking around the diner to try to come up with an analogy that could help her healthy friend understand the impact lupus has on her days, Miserandino gathered up all the spoons on her table and tables nearby and gave her friend a bouquet of spoon cutlery: Here you go, you have lupus. She went on to describe how each spoon represents a unit of energy, and a person with a chronic illness only has so many units per day to use. Some daily tasks cost one unit, others cost two or three – but when the spoons are gone, the patient is done for the day. Maybe they can borrow from tomorrow’s spoons, but then they start tomorrow with less units of energy to spend that day.

It was a brilliant analogy, and many patients felt relief that someone could put into words an effective way to help their loved ones understand what they may or may not be able to do in any given day by sharing how many “spoons” they may or may not have.

However, Miserandino’s essay was published at the dawn of the social media age, and in an effort to maintain engagement, social media companies adopted a ‘divide and conquer’ mentality by creating new features for users to divide themselves into digital groups of other like minds. As the age unfolded, the innate, hard-wired neural reflex to divide ourselves into digital villages took over, creating an echo chamber where the individual self slowly fades away into a collective mob that uses ‘likes’ as validation and comments as pitchforks. Soon, those who may not fit the assigned village narrative decided to step away, or silently watch from afar as to not find themselves on the receiving end of an often-humiliating public verbal lashing.

Of those many villages, one became known as “The Spoonies.” While it may have started as a way to find camaraderie in their shared patient experiences, the very industry that profits off their continued pain capitalized on the identity politics which have ruled the 21st century’s discourse and turned the ‘spoonie’ phenomenon into something else altogether. In this village, to be a ‘spoonie’ means to highlight the most painful parts of the patient experience while glorifying those traumas as empowering; rather than coming together to fight for better treatment options and cures, instead, the rallying cry is centered around calling out the ‘abled’ system that purportedly seeks to oppress those who are disabled.

What’s more, the ‘spoonies’ in this village must align with the messaging of one’s patient foundation, including buying t-shirts for foundation fundraisers that say, on one hand, that this disease is painful, debilitating, stressful, and incurable, and on the other, telling the patient to love their diseased guts:

In the Honestly podcast episode Does Glorifying Illness Deter Healing? Freddie DeBoer succinctly discussed this phenomenon as ‘the gentrification of illness.’

This isn’t to say that every patient feels that way – in fact, most do not – and that includes many patients who might be categorized as ‘influencers’ who openly share their patient experience on social media. I know many, and I am grateful for their voices and vulnerability. Some of them share their experiences as a call to action for better treatment options and cures, while others use their platform to comedically highlight the absurdity of navigating day to day life while dealing with a debilitating disease – a far cry from glorifying its presence. What’s more, the vast majority of patients out there aren’t online, and if they are, they aren’t ‘influencers’ nor are they discussing their patient experiences; they are quietly living their lives, doing everything they can to get out of bed every day and go to school and work, and they are scouring the internet for new research and alternative treatment options that will allow them to thrive. These patients may use ‘spoonie’ as a reference or to share the limitations of their current state, but certainly not as a central factor of their identity.

However, of the many issues plaguing our era, the idea that when a new cultural trend or phenomenon is identified as potentially problematic, it is overblown by the loudest and angriest who form a counterattack that the entire “community” has been “harmed.” This over-generalization takes away agency from the individual, replacing it with groupthink – and those who write the narrative demand that their perception is the only true and just one to have. However, that is simply not the case – though this is how many patients on Twitter responded to Suzy Weiss’s recent essay Hurts So Good – an important essay that asks what impact online patient communities have on individual patients’ well-being. This essay, and the patient perspectives in it, were met with backlash that can only be described as toxic – a word I do not use lightly in an era of its overuse.

While some patients read the essay and surmised it as a ‘hit job’ on the chronically ill, many admittedly did not read the essay at all – stopping short to describe what they perceived as ‘ableism’ and ‘appropriation of indigenous language’, rather than respond to the substance of the essay itself – or said that they didn’t need to read it to know that it is harmful. With the rise of grievance politics and self-victimization, this population of patients has developed a fixed mindset that not only refuses to entertain ideas that differ from their own – but won’t even attempt to learn what those ideas are in the first place. This collective mindset embraces a disablement narrative, and in doing so, it rejects the potential fullness and abundance of existence that can only be found when leaving the comfort zone of what we know – and it would bode well for patients to revive a sense of curiosity for what that life may entail, who knows, they might even find it.

Those who viewed it as a ‘hit job’ on patients said that the essay suggests patients are ‘faking’ their illness – missing the point that this essay isn’t about girls faking illness, but it is about the impact that our psychological state has on our physiology – and the worsening of both symptoms and pathology.

While showing support for Weiss’s essay, I shared that two things are true: inflammatory diseases are running rampant, and we are living in an era where social media perpetuates the identity of illness, and that the negativity loop from these online forums, where trauma, rage, and sadness generates the most engagement, has a direct impact on the brain-body connection and can result in the manifestation of worsening disease.

In the days that followed, I found myself also on the receiving end of the collective fury and was told that my perspective amounted to “eugenics fascism” and “thanks for letting everyone know that you’re completely and utterly worthless.” I was accused of “pimping snake oil” to make money off patients. Others said that it is “healthy to accept being disabled and chronically ill.” One woman said that she knows many patients who “waste their lives chasing cures that don’t exist” and that doing so is a “direct result of ableist attitudes like yours.” Many lambasted the idea that the brain can influence the body and that stress is not the cause of disease, nor does it worsen its pathology.

The research, however, isn’t on their side.

The Journal of the American Medicine Association (JAMA) published a report that people with severe stress disorders are 36% more likely to develop an autoimmune illness. Comparatively, those with PTSD are 46% more likely.

A study by Dr. Martin Picard, a psychobiologist at Columbia, says when dealing with acute or chronic stress, our mitochondria become damaged, leak into our bloodstream, and in turn, can lead to inflammatory disease.

Meanwhile, Dr. Steven Maier of the University of Colorado-Boulder found that stress and infection activate overlapping neural circuits and cause an increase in cytokine IL-1.

Over at the Technion Institute in Israel, Dr. Asya Rolls found that the brain encodes trauma as memory in tissue and reactivates an immune response when reintroduced to the trauma. Specifically, what happens is that neurons in the insular cortex encode immune responses in tissue, and retrieve that information when triggered, causing acute colitis.

Two decades after Dr. Kevin Tracey’s discovery of the inflammatory reflex, while working in Tracey’s lab, Dr. Sangeeta Chavan found that the brain stem stores both anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory neurons and releases those signals by way of the vagus nerve to the spleen through the mechanism of the inflammatory reflex – further elucidating the pathway of Tracey’s discovery that connects the brain to the immune system.

The mindset that the brain and body do not communicate with each other and alter each other’s function exemplifies the failure of our medical establishment. In modern medicine, health lives in a vacuum, compartmentalizing the ‘self’ into specialties separated by organs, systems, and functions, like a car broken down for parts, rejecting the mechanical interdependence of those parts, while the role of the brain (and its response to stress) as a cause of disease is blatantly rejected. Not only has this been a disservice to sick patients, but to society itself: our culture divorces thought from outcome, removing the self from the cause of what ails us.

This is not to say that tragedy and disease can’t happen at random or have an external cause, but it is to say until we accept the entire self as an interdependent system that interacts and influences each compartment through the balance of cytokines, neurotransmitters, and hormones and recognize the role the brain plays in signaling each of those based on our individual response to our circumstances — we will continue to use Band-Aids to cover what we refuse to address at the root.

The fact that some patients viewed the idea of the brain-body connection as “snake oil” is a result of an insecurity that patients very understandably have. Historically, women and minorities have not been believed when describing their physical pain – especially women whose physical and psychological ailments were labeled as ‘hysteria’ by physicians. Though that term is no longer in use, patients are often still met by this mindset for years before they can attain a proper diagnosis and treatment.

Many of those who responded to both Weiss’s essay, and my response to it on Twitter have the word “disabled” in their Twitter bios, a badge to wear in an online community that proclaims to be “incurable” – the idea being that if a person is currently unable to control their own situation, it is therefore permanent, and the best way to meet it is to nurture its presence. Gone are the days of using one’s adversity as a challenge to forge a better existence.

As of September, it has been twenty years since I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and inflammatory arthritis. This weekend I thought of that young girl relearning how to walk with the assistance of a walker, up and down the hospital hallway with a physical therapist holding her arms up horizontally beneath my armpits in case I fell. I thought about my husband putting my deodorant on for me because I couldn’t bend my arms enough to reach, nor could my hands grasp the canister. Those memories flashed from the far corners of my mind as I painted doors in our old house on Saturday, crouching down to carefully cut in along the edges of the hardware at the bottom of the door, no longer bound by the limitations of an inflamed, diseased body. It is these small, simple freedoms I savor most.

Every day we make choices that alter the outcome of our existence. While we may not always be able to control a present situation, we are always in control of our response to it. Sometimes, no matter how hard we fight, the ending of the story may not work out the way we hoped – but sometimes it does, and we owe it to ourselves to meet our adversity as a call for what has the potential to become an epic adventure.

I have never needed to know what’s at the end of the path for me to venture down it, and it is that mindset that led me to the other side of the world to treat my disease with electricity.

When I memorized the poem How Did You Die at only fourteen, I knew it would become the manual by which I would meet the circumstances of my life. Cooke used his ageless wisdom to forge a how-to guide for those who came after to not necessarily overcome adversity, but to dance with it, and become better for it. Whenever my time comes, whether “death comes with a crawl or comes with a pounce, and whether he’s slow or spry,” I know that I will have met the conditions of my existence well.

That is all any of us can hope to do – but to do so requires each of us to first view our adversity as the start of what could become a great adventure – and then set out on a journey to make it so.

Luv your work, Kelly! ~Joe P. 🥬🥬