Helmholtz, the speed of nerve conduction, and the phenomenon of ableism.

“Each individual fact, taken of itself, can indeed arouse our curiosity or our astonishment, or be useful to us in its practical applications.”

German physician and physicist Hermann von Helmholtz was a man defined not by any one particular field, but rather as a visionary who not only was able to see the interconnectedness of disciplines but also forge discoveries in the marriage of many. He once wrote, “Each individual fact, taken of itself, can indeed arouse our curiosity or our astonishment, or be useful to us in its practical applications.”

What a way to exist on this plane — and to even utter such beauty suggests that Helmholtz had a daily practice of cultivating curiosity, astonishment, and utility as a means of forging meaning in his work, and life.

His first major achievement in 1847 had to do with the conservation of energy, stemming from his study of muscle metabolism. Helmholtz was also riveted by how physical stimuli translate to sensory perception, and his early experiments aimed to uncover the ‘psychophysical laws’ by understanding the relationship between physics and psychology — the physical energy of something and the appreciation thereof.

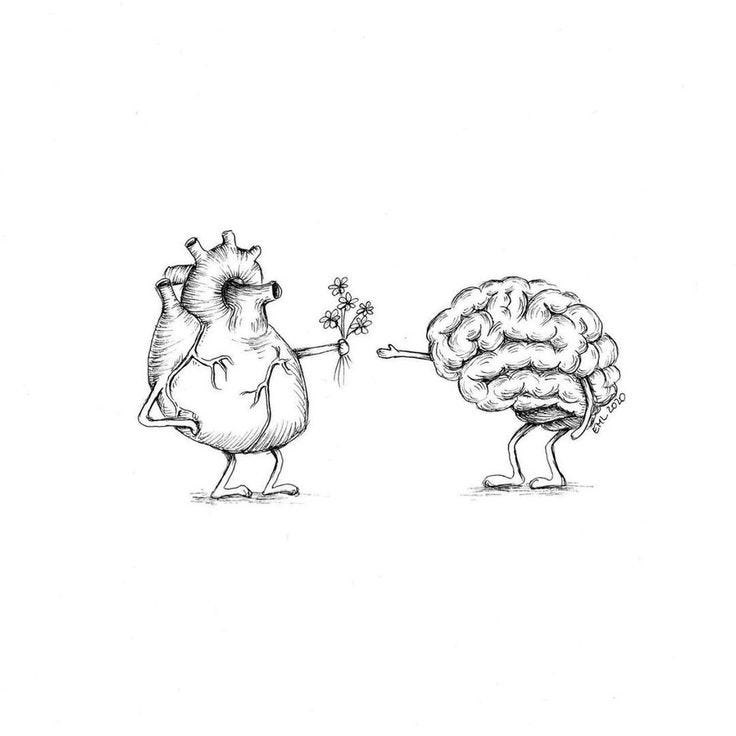

A philosopher as much as a scientist, he also sought to understand the unity between the mind and body and was interested in nerve physiology and electromagnetism. Helmholtz believed that all physiology is mechanistic, and sought to better understand those mechanisms through measuring the speed of nerve conduction.

In her literary masterpiece Figuring, while discussing Emily Dickinson’s deeply passionate love letters, Maria Popova writes of this phenomenon of not only the mind and body’s unity, but also its communication via electricity:

“Helmholtz measured the speed of nerve conduction at eighty feet per second. How unfathomable that sentiments this intense and emotions this explosive, launched from a mind that seemed to move at light-years per second, can be reduced to mere electrical impulses. And yet that is what we are — biomechanical creatures, all of our creative force, all of our mathematical figurings, all the wildness of our loves pulsating at eighty feet per second along neural infrastructure that evolved over millennia. Even the fathoming faculty that struggles to fathom this is a series of such electrical impulses.”

And here we are, a mere 170 years later, living in an era among great scientists and visionaries who have so exquisitely mapped the neural infrastructure connecting our mind and body, elucidating over the last twenty years the neural communication that occurs when something takes our breath away, every skip of our heartbeat when our eyes perceive the sight of someone we love, and the subconscious categorization of busy neurons storing within our brain tissue the memory of our worst traumas, rewiring synapses to perpetuate the cycle of our internal communications, the thoughts we think, and the words we say — all coming together to create the reality we each live among.

If we could have the opportunity to sit down with Helmholtz today and ask him if the words that we utter about ourselves, and others, matter in regard to the communication occurring within our neural infrastructure, and how we perceive ourselves, the world, and our place in it, I think he would say:

Yeah, no shit.

Does this mean we can think or speak ourselves healthy?

No, not per se. However, the belief that we could become more than our greatest current limitations alters our behaviors — and those behaviors could lead us to places beyond our wildest dreams.

It is with this in mind that I regularly grapple with a particular phenomenon within our 21st-century vernacular, and that is our modern, unique ability to find a negative connotation for words that previously weren’t — or, in other cases, expanding the definition of negative words to include a larger pool of people who we simply don’t like or don’t agree with, rather than understanding that we all arrive at different points based on experience.

But sticking to the former — changing the definition of words — and doing so by adding an -ism to the end and yelling at everyone until they’ve internalized a collective trauma around the redefined word whose umbrella generally provides cover for an oppression to be reckoned with.

As an individual who wears many hats, with one of them being ‘patient advocate,’ the word that I often hear is ‘ableism.’

In an era that tells us that words are harmful (and silence is violence), it is difficult to identify what is actual harm and what is perceived harm. I imagine Helmholtz setting up an experiment to measure the physical stimuli’s impact on the sensory perception, but unable to identify exactly the source of harm of this particular physical stimuli:

Is it the sight of ableist words on the screen?

The intonation of the spoken ableist word?

A couple of week ago, I sat down for a moment to look up the exact definition of the root of this -ism. Before I could finish typing the root word, Google assumed I was aiming for the -ism.

Before we dive into the problem with the -ism, though, let’s line up the facts by defining the root word ‘able’:

From the Latin word ‘habere’ — to hold.

‘having the power, skill, means, or opportunity to do something.’

‘having considerable skill, proficiency, or intelligence.’

Synonyms:

capable, competent, equal, fit, good, qualified, suitable.

Antonyms:

Incompetent, inept, poor, unfit, unfitted, unqualified.

Or, used as an adjective suffix:

capable of, fit for, or worthy of.

Now the -ism:

Ableism: Discrimination against people with disabilities. Characterizes persons as defined by their disabilities and as inferior to the non-disabled. On this basis, people are assigned or denied certain perceived abilities, skills, or character orientations.

Undoubtedly, there is a need to enact protections, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act, IDEA, and 504 Plans to provide equal access to education, employment, and so forth that would otherwise lend to unjust restrictions or discriminatory practices.

But that’s not what the latest redefining of the word is addressing. The latest connotation is less about equal justice under the law, and more of a hand-slap for communication or behavior that is perceived as superior to a person protected under the ADA.

The problem is when we go back to the root word ‘able’ and revisit its definition, the argument of someone being ‘ableist’ or an idea labeled under the umbrella of ‘ableism’ means that the other person is inherently all things opposite of the root word of ‘able.’

Rather than providing the inner self with access to words like:

capable, competent, equal, fit, good, qualified, suitable —

instead, the -ism sentences the inner self to surrender to identifying with the antonyms:

incompetent, inept, poor, unfit, unfitted, unqualified.

And ‘ableism’ disqualifies the potential for having a quality where we can add the adjective suffix — to be capable of, fit for, or worthy of.

My problem with the phenomenon of ableism isn’t that there is no need to address the problems of those experiencing disabilities — there absolutely is.

My problem with the phenomenon of ableism, instead, is that the psychosocial phenomenon of labeling people, actions, or ideas as ‘ableist’ meets the world with a deficit mindset, and sets a precedent for what Helmholtz may have considered ‘psychophysical law’ that disempowers a person’s inherent abilities, and diminishes the potential for accessing those currently unavailable — that may otherwise be — if growth mindsets altered behaviors.

This psychosocial precedent inherently views the self as having less ability, and prophesies a future that maintains any current limitations a person has rather than chasing any potential for progress.

It is a phenomenon devoid of hope, and it is based in insecurity, nihilism, and a fixed mindset that believes that we begin and end with all the tools, talents, and abilities we will ever have and therefore cannot seek more — and to break from the ranks to try to recognize currently accessible synonyms of ‘able,’ or to seek access to any of the other aforementioned, means a loss of camaraderie within the accepted groupthink that has spoken for the individual identity based on the collective rules of that identity.

As we move forward in this century and think about the world we want to leave to those who come after us, and on behalf of both our individual and generational legacy, let’s remember that words matter.

We are a sum of the words we’ve previously said or thought about ourselves and others, and we will later become the sum of the words we are saying and thinking now.

Yes, words are indeed harmful — but only the ones we use about ourselves.